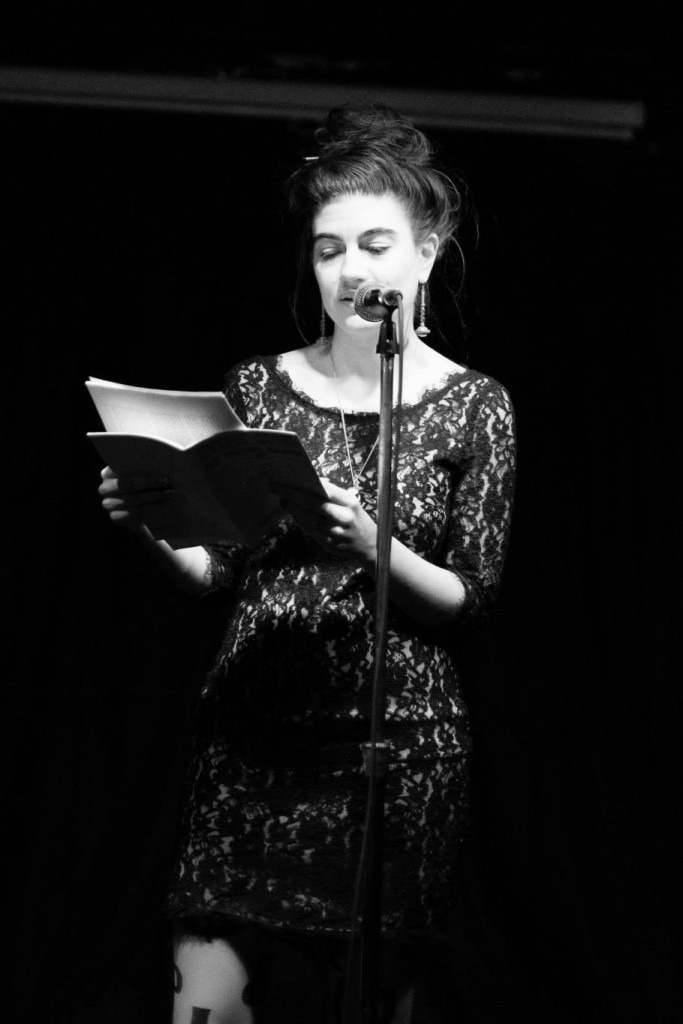

Kimberly Ann Southwick is a feather not a flower. She is the founder and editor in chief of the literary arts journal Gigantic Sequins. Her poetry has been published in a variety of online and print journals. She has two recent chapbooks, every song By Patsy Cline (dancing girl press, February 2014) & efs & vees (Hyacinth Girl Press, October 2015). She lives in Breaux Bridge, LA, where she is pursuing her PhD in English/Creative Writing at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

Toni Loeffler: So you just moved to Louisiana?

K: I did! I guess I drove down the 17th, and my orientation was the next morning.

T: Oh, wow. Did you have a place already, or?

K: Yah, we rented a place on Craigslist. We had someone check it out, to make sure it was real.

T: So, then you’re teaching, then, too, right?

K: Yeah.

T: What do you teach?

K: First year writing, which I’ve taught before. Eventually I’ll be able to teach some other courses, maybe even a creative writing class. I guess that just comes with time.

T: Nice. So you’re originally from Philly, right?

K: Yeah, I just moved here from Philly.

T: I know a little about Lafayette. It’s a French-Cajun area, right? What do you think about it? Has it been a huge change for you?

K: I’ve lived in cities for a really long time. I’ve lived in Boston for my undergrad and New York for my master’s program, and I adjuncted in Philly forever, so living in the suburbs is weird. Living down south, I’ve never lived down south before, so that’s different. I had to go to Walmart to pay a bill—that’s what they told me on the phone.

T: (Laughs) That would be culture shock, I would imagine. I’m originally from the South, so I…yeah. I got out. I moved to Oregon nine years ago.

K: There’s a big truck that comes, and it sprays bug spray throughout the air.

T: Oh, probably for mosquitos.

K: Yah, that was interesting. I never saw that before. But there’s culture down here. One of the reasons I thought that Lafayette was really neat when I was applying was the culture. I thought that maybe I’d move to the suburbs and hate my life. But there’s an art crawl this weekend, and there’s art and food and culture here that normally you would have to go to the cities for. Which, of course, Lafayette is the third largest city in Louisiana, but still.

T: So, why did you decide to go for your PhD?

K: As an undergrad, I always wanted to get my PhD. I had a really good advisor at Emerson, Maria Koundoura, and she saw me being a professor. She told me, “You should get your PhD,” and so straight out of undergrad I applied to PhD programs, which are impossible to get into, and I didn’t get into any of them. But luckily, at NYU you can apply to both the PhD program and your Master’s, so I went and got my Master’s in English. And then I adjuncted. For like five years. And that will really bring you down a notch and make you think about your life. And I just couldn’t do it anymore. So, I figured I’m either going to keep going and get to a point where I can apply for a full-time professor job somewhere, and have a chance, or I can do something else, like I could go down a different path. So I applied two years ago and didn’t get in anywhere, and then I went back and rethought my application and rethought what I was sending and where I was applying. And I applied and got into ULL. So I want to teach full-time as a profession. At the college level. I don’t know if I could…everyone says I’d make a good elementary school teacher. I think that’s a lie. I’m not an elementary school teacher. I couldn’t do it. Even high school. Unless they’re honors kids. And you’re not going to go in and punish all the kids all at once, so.

So, I figured I’m either going to keep going and get to a point where I can apply for a full-time professor job somewhere, and have a chance, or I can do something else, like I could go down a different path.

T: You have to pay your dues as an adjunct. I can see why that would be hard. It’s already disheartening to me. I mean, I just want to do what I love.

K: I was very upset with my Master’s program. They were like, Oh, don’t even bother getting your PhD, it’s not worth it. But all you can do with a Master’s degree is teach adjunct, that’s all you can do. And actually right now there’s a really good movement happening to unionize adjuncts as kind of a first step to getting better pay and better benefits. And specifically at Temple University, where I taught briefly. It’s really cool what’s happening there and also terrible at the same time. They’re trying to unionize, and the Temple administrators won’t let them. And they’ve gone as far as taking them to court a bunch of times because they’re trying to unionize and come together. And the Temple administrators have gone so far to say that adjuncts aren’t faculty. Which I’m not sure what I was when I was there if I wasn’t faculty. Considering over 50% of the people who are adjuncting there are their faculty. It’s this corrupt system where they keep offering less and less full-time positions or hiring adjuncts to do the labor. You’d think that our educational system wouldn’t be that way, but it is. It’s really interesting what’s happening there right now. I was sad to leave to be so far away from it, but I still forward all the petitions and everything, but I’m not really there. Not that we really have it that much better as grad students, but they pay my tuition. So, you know, not to complain. So don’t worry. The point being, I think that there’s good things happening right now.

T: It’s so refreshing to hear an optimistic voice.

K: Keep being involved, don’t keep your head down. If that’s your future, it’s important that you pay attention to what’s happening. Don’t feel discouraged by these people who say that the job market’s bad. Feel encouraged to make the world a better place.

If that’s your future, it’s important that you pay attention to what’s happening. Don’t feel discouraged by these people who say that the job market’s bad. Feel encouraged to make the world a better place.

T: Well, let’s talk about your upcoming chapbook. I have to tell you, my favorite poem is “Mortgage that Shit.” I love that poem. And I really enjoy your imagery throughout, too. I’m really curious to know the process of how your chapbook came into being and how you melded different themes and imagery together. I guess what I’d like to know is if your chapbook was something that came all at once or if it was something that you put together slowly over time?

K: This chapbook, specifically, is something that happened over time, for sure. It’s part of something larger that I was originally sending out as a larger manuscript, but that’s incredibly disheartening sometimes. If you’re going to send something out as a larger manuscript, they’re going to charge you a fee, and you don’t always get anything from that fee, so that limits what I would send. Like I would only send it to free open reading periods, which barely exist, or to somewhere that I would actually get something out of it. It’s really hard for me to just throw $20 at a publishing company. I like supporting them and everything, but you know, give me something. Give me a book! So, I had this large manuscript that was in three sections. So because it all came from a larger manuscript that I had been working on since, I would say, well… I had just left New York, so that would be like over the past five or six years. Maybe five years because I sent it to Margaret last summer.

Some of them were my Philly poems, and some were things I wrote my last couple of years in New York, and some of them were relatively new.

Specifically “Mortgage that Shit,” I can talk about that poem. That was before I was engaged, I think, when I was ready to be married. Before that, I had a different idea of it, and I was tired of everyone getting married, but not for any reason that made any sense to me. It was completely irrational. So it was kind of me just writing what I thought about it, me being irrational toward that idea. Where some of these poems are from before I was even in a relationship. I think I did “Mortgage that Shit” before I was even engaged. Well, you know, the beginning stanza I ended up cutting a bunch of times because I was writing “It’s raining outside,” and I’m just going to use this to start my poem. And the rest of it is just about, you know, being a boring adult. Our kids are going to be normal kids. And then just turning that on its head—no, they’re not going to be normal, but you know, they are, no matter what. So we’re just going to end up falling into line. But you’d like to think your experience in and of itself is special. So we’re going to listen to the Beach Boys, and we’re going to listen to an old record player, like we’re cool somehow. I guess the reason I put it last is because everything felt like it added up to that one. That one, and then there’s another one. I think it’s in this chapbook. The one about getting my hair done.

So we’re just going to end up falling into line. But you’d like to think your experience in and of itself is special. So we’re going to listen to the Beach Boys, and we’re going to listen to an old record player, like we’re cool somehow.

T: Oh, yeah, that one’s earlier on.

K: Yeah, “In 24 hours exactly you will be getting your hair done.” That’s about going to a wedding. I feel like all of my imagery for the whole chapbook kind of adds up in that poem, and then the last one culminates with, “Alright, we’re just going to…we’re going to do this thing.” Mortgage that shit.

T: Tell me about “Present and Preterit.” I really like that one a lot, too. I just thought the temporality was interesting and also the way the social commentary intermingles with the idea between the public and the private selves.

K: Yeah, I feel like the whole poem started because I wanted to say something about the private selves. That was the vehicle in writing it. And then everything else that came was like, well, in order to write this poem, you can’t just come out and talk about fidelity, and public and private selves, that wasn’t enough. You need something to like bolster the poem with. So I did. I guess I was thinking about them [Lancelot and Guinevere] in like a future context. I like their characters. I keep coming back to them a lot, again and again in my writing. I think this is the only time they end up in this chapbook, though. Which is interesting. I forgot about Guinevere and Lancelot and Arthur. I love The Once and Future King. I’ve read that at least twice. It’s one of those that I go back to and reread my favorite passages. I guess I just like that they can all be so friendly even though they were doing something shitty. So I kind of reimagined them in the now, and I had just started teaching a grammar course. One of the first courses that I ever taught as an adjunct was an upper-level grammar course at Rowan University that all English majors and Education majors had to pass. It really boggled my mind that there really is no future tense and just what that says about our life in general. We make the future tense just by throwing ‘will’ in front of the root word, so you know, ‘to go’ is ‘will go’. Or shall, you could also use shall. So, really, there’s no conjugation. It’s just there. So the idea that there’s no future. And I feel like my students never understood that there’s no future tense, no matter how many times I tried to explain it to them. We don’t conjugate it, so we can call it a tense, but it’s not really a tense. Which is subjective, and different grammarians probably think differently about that. But they just weren’t interested. So I imagined them hearing that there’s no future and them drifting off. So yeah, I intuited Gwen and Lance in this future and just went with it. So the title’s a grammatical reference. Preterit, I think, is simple past. So it’s all of this is all together. The idea that nothing ever changes. These tropes exist because they get replayed again and again and again. So as much as we feel as though we’re being progressive, are we really being progressive? I don’t know. I guess I just really like the idea of reimagining them [Guinevere and Lancelot] somewhere where there’s a video camera, where they’re nervous. Does Arthur know? I’m pretty sure he knew, and he was just like, Whatever, I’m just going to pretend like I don’t know that this happened. Maybe that’s how the future functions. We’re just like, hmmm, we’ll come out on the other side. Everything’s either going to be okay, or everything’s not going to be okay. And no matter what, you just have to be like, Alright, let’s deal with it.

Everything’s either going to be okay, or everything’s not going to be okay. And no matter what, you just have to be like, Alright, let’s deal with it.

T: Yeah, it doesn’t matter. You can get all worried, or you can just let it happen.

K: Yeah. I feel like so many things are getting better. Gay marriage, hooray! But all the bees are dying. Bad. I’m writing a series of poems right now. There’s seven of them, and they’re entitled, “The World’s Going to Be Okay.” I guess this is something I come back to again and again without realizing that I’m writing about it a lot.

T: Tell me more about those.

K: They’re all about me talking to my Nana. The “Dear Nana” poems, and she’s like, “The world’s so terrible.” And I tell her, “No, we have all these good things.” And I’m always trying to convince her that everything’s going to be okay. And in thinking of that and literally having these conversations with her, I’m just defending my generation, but at the same time, all these horrible things that are happening right now still haunt me as well, but I just don’t want her to think she did something wrong by having children and letting them have children and encouraging her grandchildren to have children. These [Efs and Vees] were the pre-marriage poems. Now that I’m married, I think, Do I have kids? Do I not have kids? I think that’s my big contemplation in my life, so these now are like Do I get married? Do I conform or do I do my own thing? Can I get married and not conform? Whereas the new ones are Do I have kids? Do I not have kids? I guess it’s like classic women’s poetry.

T: It’s very beautiful poetry, and I was very happy to get a chance to read it. Is there anything else you wanted to add or anything that we didn’t cover?

K: Yeah, working with Margaret at Hyacinth Girl Press has been awesome, and I’m not just saying that because she’s publishing me. I have a previous chapbook that I put out, which was fine. I don’t have anything bad to say about that experience. But specifically, working with Margaret at Hyacinth Girl Press—she’s great. She’s not just a selector, she’s an editor. She went through and really thought about everything that was going to be in my book and gave me a lot of input but also a lot help, such as with figuring out the cover. We organized a reading together in Pittsburgh, so I got to go hang out with her and do a reading for her press and Gigantic Sequins, which is the literary journal that I run. I don’t know if she knows how important she is to the feminist literary community she currently is, but she is doing a really good job. I wasn’t really paying much attention to that when I first submitted my manuscript, and now I’m really happy to have had the chance to work with her. It really feels like someone was there for me. She knows what she’s doing, and maybe she’s a little shy about that. One time she posted something on Facebook, where she was questioning being an editor, and I was just, “Yes, you’re doing a great job.”

I don’t know if she knows how important she is to the feminist literary community she currently is, but she is doing a really good job. I wasn’t really paying much attention to that when I first submitted my manuscript, and now I’m really happy to have had the chance to work with her. It really feels like someone was there for me.

T: That’s awesome. It’s important to show gratitude to someone like that because not everybody is that caring.

K: Yeah. And she wasn’t just, “Hey, I want to publish this.” She was like, “Here is what I loved about this.” When the chapbooks were accepted, she did this whole ‘Chapbook Thunderdome’ thing, where she pitted the chapbooks against one another like it was March Madness and then revealed who made it to the next round. It was a really fun, interesting way to get excitement going over who she was going to publish over the next year. It was a cool thing to be a part of.

Toni Loeffler moved to Wichita from Eugene, Oregon, where she graduated at the University of Oregon with a BA in English. She is a first-year MFA at Wichita State and writes poetry. Some of Toni’s favorite poets include Sharon Olds, Philip Larkin, Cate Marvin, and John Donne. This is her first interview for mojo.