*

In my child’s mind:

I set out of the town, satchel in tow, not stopping until after I pass through the glinting tin-roof shantytown of Cowdray Park. Behind me, the orange sunset unfolds like a huge petal through the darkening sky. My mother frantically calls all of my friends’ parents. Have you seen him? Have you seen him? Have you

*

Zimbabwe, 1990

My father left seven days ago, headed towards several small villages between Bulawayo and Beitbridge. He often took trips like this, packing up a generator, petrol, water, and sleeping bags, and heading out into the wild, sometimes with one or two Ndebele men, sometimes alone. Rarely was he gone seven days.

*

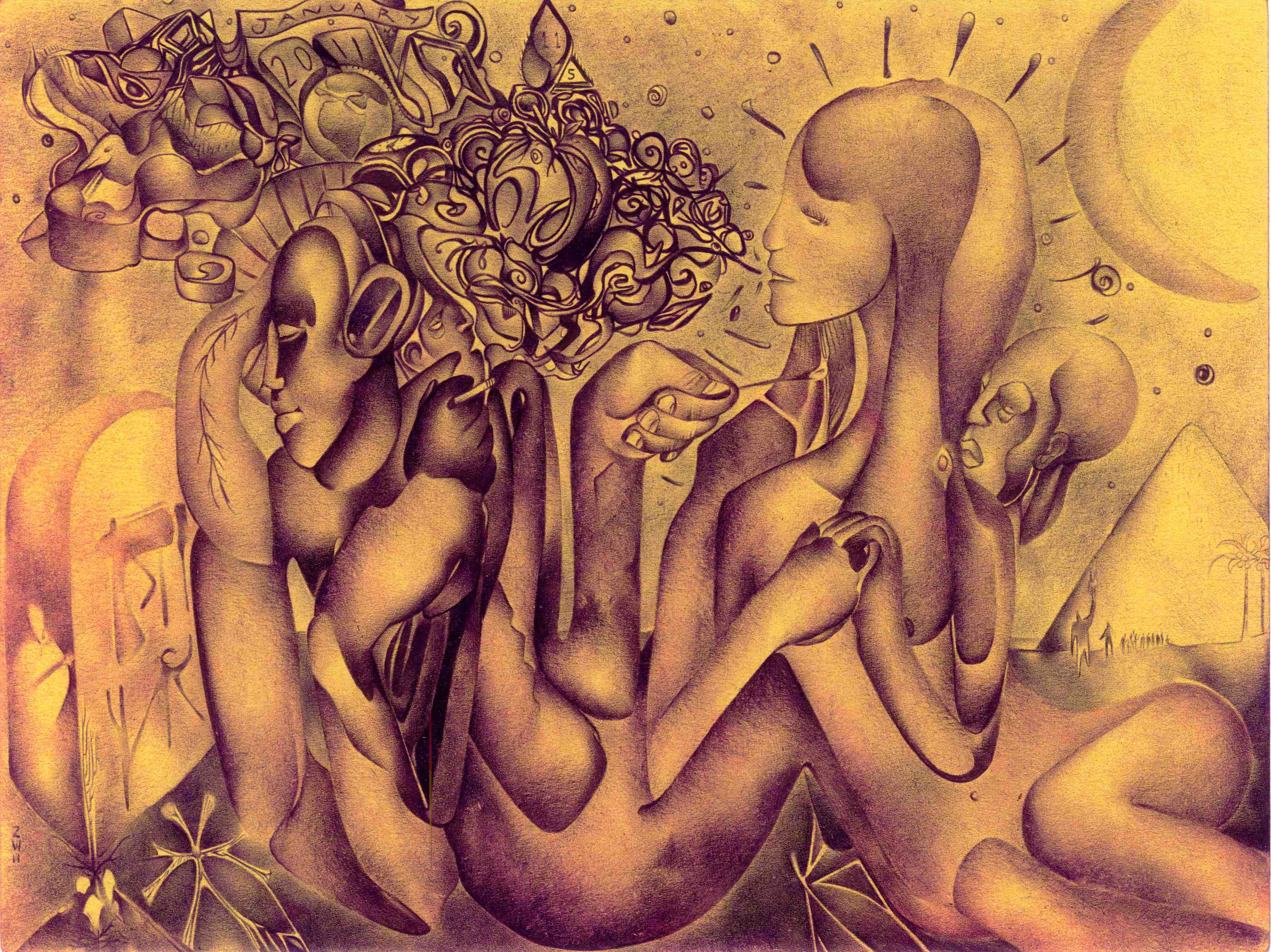

The child’s dreams possessed him ever since his father left. All night he twisted beneath the blue ceiling and felt the hand of God, cold like the million-starred sky, pressing down onto him. Oftentimes the child would wake, choking on his tongue, his mother running into the room from the noise and screaming as he turned purple. Doctors prescribed phenobarbital, describing his symptoms as “seizure-like.” Hating the way they tasted, the child fed the pills to the enormous turtle in the yard and watched as it swooned and fell suddenly asleep.

*

God called my parents to serve as missionaries sometime around 1983. My sister Jennifer had just been born. My parents clasped their hands together in prayer for hours, their joints stiff in the language of supplication. They wanted God to tell them where to go, what place in all of time and history was apportioned for his purpose through them. Though I can admire their faith, and I too consider myself a Christian, I could never be as devout as my parents; I like to know, not trust.

*

I was born in November of 1985. My brother Steven followed three years later, when we left for Zimbabwe. I cannot accurately describe the bewilderment of my father’s parents; they simply could not see why God was sending their son and his wife and their three grandchildren to darkest Africa. I’m still not sure if my grandfather ever forgave my parents for their decision.

*

In my child’s mind:

As I leave the town, I see the head of a dog. Ants have ravaged its tongue. I imagine crawling inside of the mouth seething with ants to find my father. I can almost feel the ants telling me yes, yes my father is inside, please do come in. Already I am thirsty and the ants look so cool in their shiny, liquid husks, like water at midnight. I imagine the water engulfing me until I am black. The water creeps up, inch by inch, tingling between my legs as it rises. I know this must be a mistake, I can’t let the water cover my mouth. I see the ants’ little heads, their antennae touching the calyx of my eyelid. The ants don’t have eyes; their little heads are smooth and twisting. All around me, they crawl, the great river of them fed from the dog’s open mouth. I open my mouth to scream. The ants rush in and flood me. My skin bustles with black water.

*

Shifting forward a few years in the chronology of things, my parents are both fluent in Ndebele and Shona, the two Bantu languages of Zimbabwe. We have a house and six dogs. Everyone is very happy. My father’s parents come to visit.

Hydroxychloroquine is the name of the anti-malarial medication we take. It treats lupus as well. My grandmother, Jonelle, begins the course of medication two weeks before coming to visit, as is standard. Fatigued from the flight, she sleeps a lot the first day. The fatigue lasts their entire two week stay. She takes the medication every day, as directed. Still she has time for her grandchildren; she takes us on walks. We name every tree along the way.

She loves us terribly, she says. We ask why love is terrible. She hurries us home.

At night, she makes strong, black coffee and lets me drink from her mug. My mother disapproves, but Jonelle says that it’s nothing, and I like it. She pulls me onto her lap. She whispers into my ear that I’m her favorite, which means, I love you more than anything.

A little-known fact about hydroxychloroquine is that in the rarest of instances, the allergy to it disguises itself as fatigue without any other symptoms. The medicine, taken as directed, builds up in your system and eventually dissolves, releasing the potent aid against malaria slowly, every day for eight weeks.

*

In my child’s mind:

The police stop me at the border of Bulawayo. They ask for my papers and I present them.

Where are your parents?

I’m looking for my father.

Come. We must take you home.

Their automatic rifles gleam and are almost white all over in the sun.

I know I have lost.

I will never find my father.

*

My father never went missing. We worried endlessly, of course, when he was gone. He ventured out to small villages hundreds of miles from phones, electricity, potable water. I don’t know how my mother handled not knowing. Trust, not knowing.

*

We receive the first phone call late at night. Jonelle is in the hospital in Memphis, her kidneys failing. Pray, my grandfather begs. Pray. My parents don’t say a word to us about it and send us off to school. Jennifer, Steven, and I are called to the principal’s office mid-morning. A family friend picked us up and drove us home. When we opened the door, my father looked up from the floor, where he knelt. He tried to get up, but his knees were stiff from hours of praying. A terrible thing has happened. All the sunshine in the room gathered in his face, his fever eyes.

*

My mother and sister found the girl’s body on their nightly walk through the neighborhood. Her muscles, leached of blood, lay rank in the dust. All of her skin had been peeled off and the internal organs removed. The skin and organs are used to make muti, or medicine. A dog ambled up to the corpse, and my mother shooed it away.

*

My parents hired a housekeeper the next week. Edna was an Ndebele woman, very tall, thin, muscular. She took the three of us to a witchdoctor for muti and didn’t tell our parents. The witch-doctor was thin, except for a stomach swollen from liquor. His breath stank of hot milk and his yellow eyes held the opaque trappings of glue. He coughed over three muti amulets in exchange for the chicken and handful of my parent’s money Edna had brought. We wore the swinging amulets beneath our clothes, and Edna kept them for us when our parents weren’t around. Muti kept the bad spirits away, but it required blood sacrifice to make. Blood spilled in place of your blood. My sister hated wearing the charm; I think she always thought of the other girl, the one who was killed so others could keep on living.

*

Those idiots, my father said.

He and I drove in the lorry toward the ice-cream shop at the outskirts of the dusty Matsheumhlope district. They had all the best flavors: Black Mamba, Green Mamba, Hippo Ice. In front of us was another lorry with three blacks dancing in the back. I could hear their music in my teeth. They stopped. A girl in a red skirt was jolted from of the lorry-bed onto the pavement. Her head split open on the road, and she shook and frothed at the mouth while a pool of purple liquid steamed around her head. My father jumped out and knelt next to her, yelling at the blacks for their stupidity. Even the driver was drunk. Praying over her, my father gathered her shaking hand into his as she died. We waited for the police to come, and after a while, my father gave a report. The others from the vehicle ululated loud into the night, as is custom for the Ndebele. They fill the heavens with their grief in hopes that it will rain down and better the soil. My father, trying to make the best of the evening, still drove me to the ice-cream shop. I licked at my Green Mamba; sweet mint filled my mouth. I kept looking at the sky in hopes of rain.

*

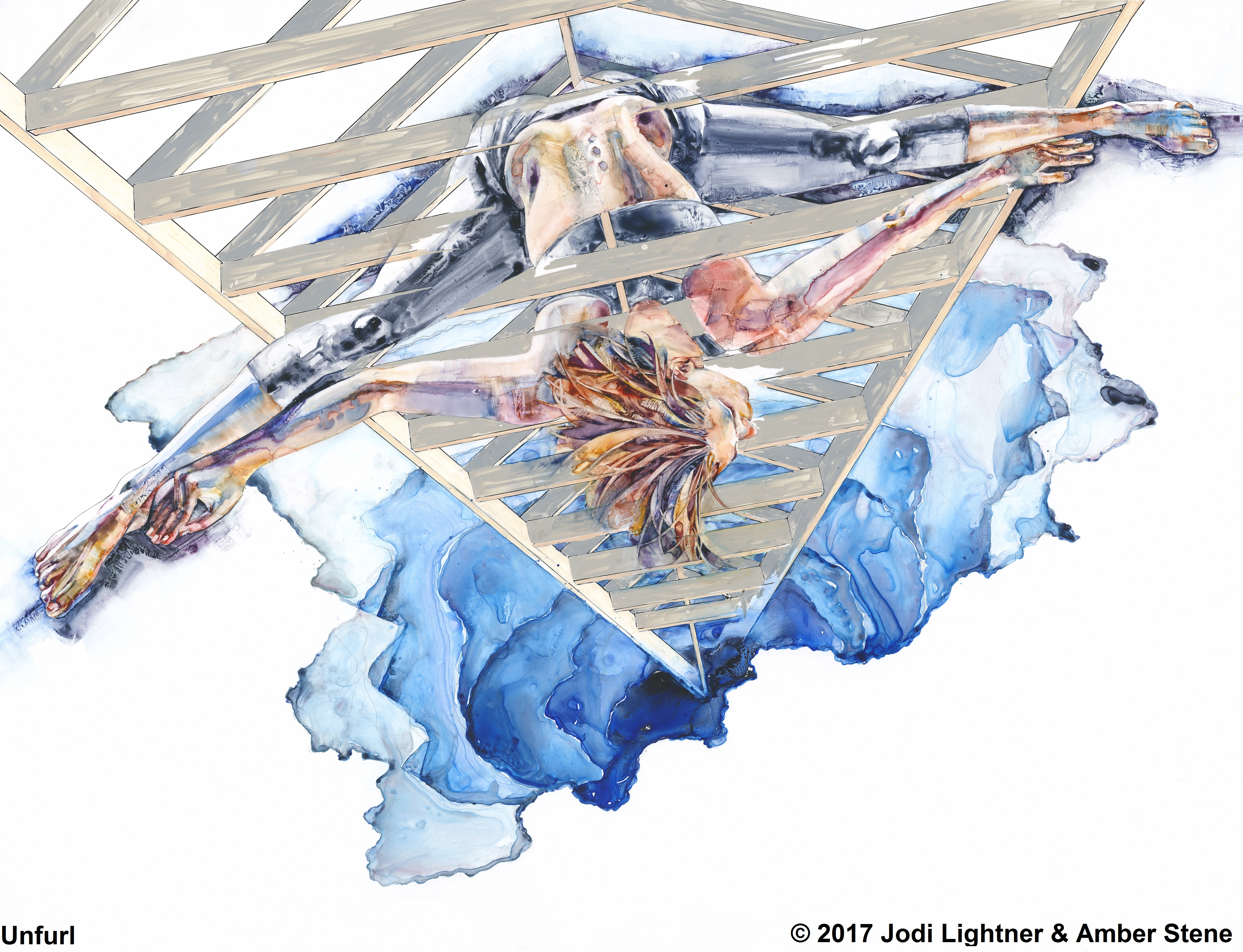

Chronology is just another way of ordering what is normally in-orderable. Sometimes, looking up from my desk to my front yard in Memphis, I see baobabs, savage, heat-ridden. The tulip poplars blink into focus, and I’m simply unable to do anything afterwards. I saw a psychologist during my first year of college, and he said maybe I had repressed much of my childhood to the point of spillover into my life now. Everything is baobabs and pangolins and soldiers and rationing. Chronology has no place in all of this. My life interrupts itself constantly with its past; nothing holds.